Compassion originates from the latin word patior meaning “to suffer with”; to share in another’s distress and to be moved to respond. As a doctor, compassion reflects a willingness to share the patient’s anguish and a desire to make it more bearable.

Compassion encompasses both sympathy and empathy. Sympathy is a statement of emotional concern whilst empathy is a deeper connection with, and understanding of, another person’s emotional state.

Compassion has long been recognised as an essential ingredient in medicine and is especially important in areas such as general practice and palliative care. It is not simply a tool for fostering a therapeutic relationship with patients – being kind and compassionate improves patient outcomes. Research shows that when doctors and nurses act compassionately, patients are more likely to divulge information, leading to more accurate diagnoses. Patients are also more likely to take treatment advice. Other clinical studies show that anxiety and fear delay healing and so any actions which reduce anxiety, such as compassionate behaviours, are likely to benefit outcomes.

May I never see in the patient anything but a fellow creature in pain.May I never consider him merely a vessel of disease.

Maimonides 12th Century

Rekha-di

Rekha is the patient co-ordinator for our palliative care team. Having spent most of her working life in a bank, she joined the team as a volunteer the year after her husband died of cancer in this hospital. She was such a committed volunteer that the director created a post for her and insisted she be paid. Although she has no medical background, her input with patients and families is invaluable because of the huge amount of compassion she shows.

I saw a 26 year old patient with lymphoma with Rekha and my consultant. It was the first time any of us had met him and it was clear that the referral to our team was late in the day. His muscles were wasted and weak, and he could no longer get out of bed. Initially I thought he was delirious – he seemed confused, was reaching out and looked agitated. After spending a few minutes with him it became apparent that he was not confused at all; he was really frightened and desperate for help. I began to run through a list of drugs in my head that would relieve his symptoms of acute anxiety. As I was doing this, Rekha went to him and put her arms around him, held his head on her shoulder and stroked his back whilst speaking in soft Bengali. The tension from his body dissolved, he closed his eyes and was momentarily relieved.

Two hours later he passed away. Although I had recognised that he was in the final stages of his illness, none of us had foreseen such an imminent death. I felt shocked and saddened, and regretted not having done more. Then I thought of Rekha-di and her act of compassion that so effectively relieved his suffering in that moment. This may have been the last kind and soothing touch he received before he died. Rekha’s embrace was far more powerful than a prescription or a doctor’s opinion written in the notes.

On many occasions Rekha has helped me to deliver bad news. She has supported me through painful conversations with families, explaining that their loved one is dying. These families were often hearing this news for the first time. She has a natural ability to connect with families and frequently shares their tears. She sometimes discloses her own loss; the reason that she feels their pain more acutely than most.

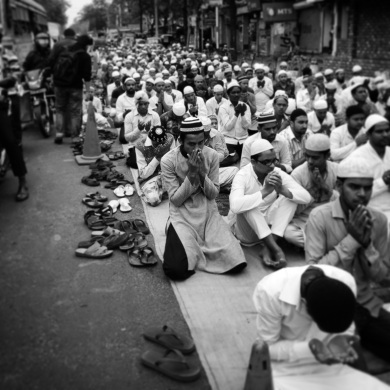

Rekha stands out for her approach in this hospital. I have met many compassionate doctors, but this is usually down to disposition rather than learnt skills. I often see bad news delivered bluntly in the corridor with little recognition of the emotional significance. Doctors behaviour is shaped by many factors including cultural expectations, training and the level of suffering they are exposed to. In Kolkata, and this hospital, the level of human suffering is far beyond anything I have experienced at home. Doctors working in India require robust defences to be able to cope with this, and distancing yourself from the emotional pain experienced by patients and families is one mechanism to remain functional at work and avoid burnout.

Rekha-di has taught me a lot about compassion this year. I now use touch more readily. This transcends cultures and languages to show concern and care. She has also shown me how to be with patients and families and acknowledge their pain without always having a solution for it – one of the hardest but most important aspects of palliative care.

F

F